Long time no see, huh! Sorry about the relatively long gap between the posts — I am currently rehearsing the tracks for my new EP, and it takes pretty much all of my time (which is the issue that might — and should — be addressed by proper practice 🤓)! Anyway — today I wanted to share a part of my workflow concerning the jazz books: how I use them, adapt them to my (sometimes not-so-jazzy) needs and make them work together with other practice routines that I have.

Here’s one of my long-time favourites: Jazz Piano Voicing Skills by Dan Haerle, one of the world’s most renowned jazz educators and pianist (he’s retired from his university job, but he’s still touring with his trio, by the way!). It’s the book that opened the Pandora’s box of 13th chords voicings — all that 7-3-5, 3-7-9, 7-3-6, all the polychord and fourthy stuff that I keep going on about here — it’s from Mr. Haerle. If you’re just starting your journey from the block chords to the new horizons, I would recommend getting this book, closing your browser tab and just diving in it for a couple of months — it will take your playing to the next level, no shit 🤭

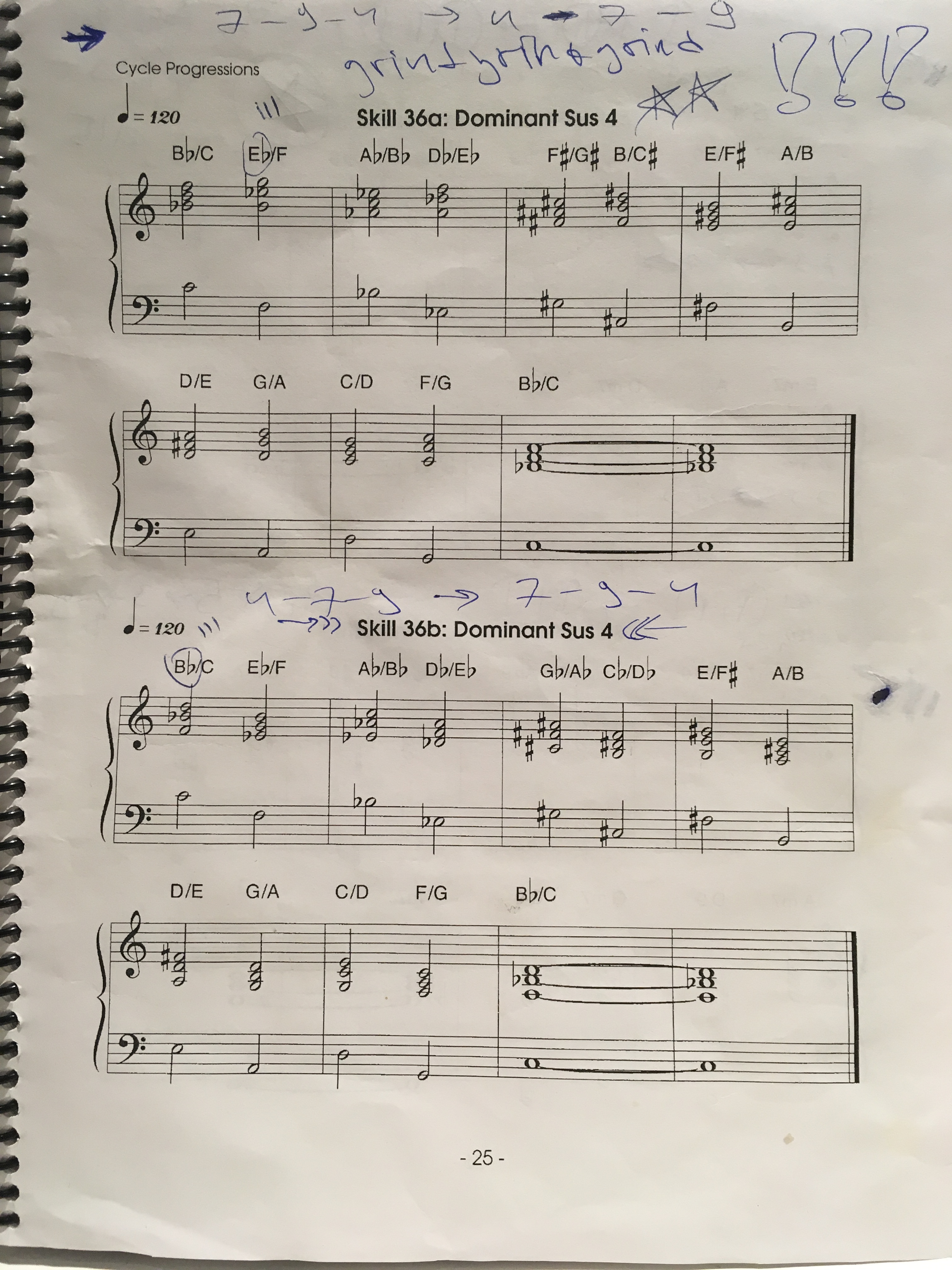

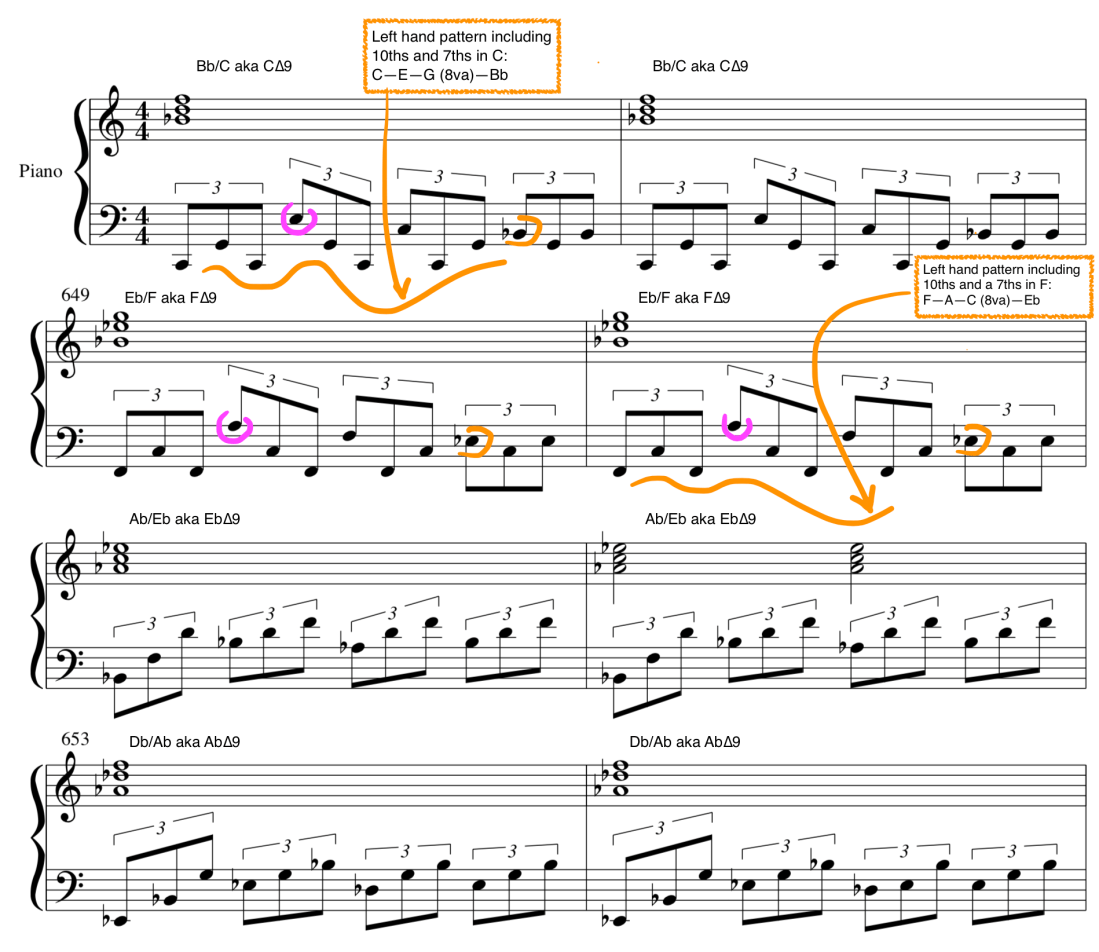

So, back to today’s topic — here’s an excerpt from the book:

All exercises there are called “skills”, and what they are is basically different types of 7th or 13th chords moving around the cycle of fourths while using the smart voice leading to ensure minimum finger movement. Sometimes the quality of the chord will also change, but in this case, it’s just the dominant chords with suspended 4ths, the left hand plays the root, and the right plays 7-9-4 → 4-7-9 pattern. You can also see that the marks that I leave in my paper books look exactly the same as the ones I have in my own sheet music here 😆

Okay, so, this is a great exercise, but after a while, it kind of gets too simple, particularly because of the left hand only playing the tonic. How can we improve that?

Of course! Instead of playing just the tonic — I’m going to play the full block chord with the left hand, which will give me the full dominant polychord sound and a very satisfying sentiment of being smarter than the jazz book. But chords are boring. Let’s arpeggiate things!

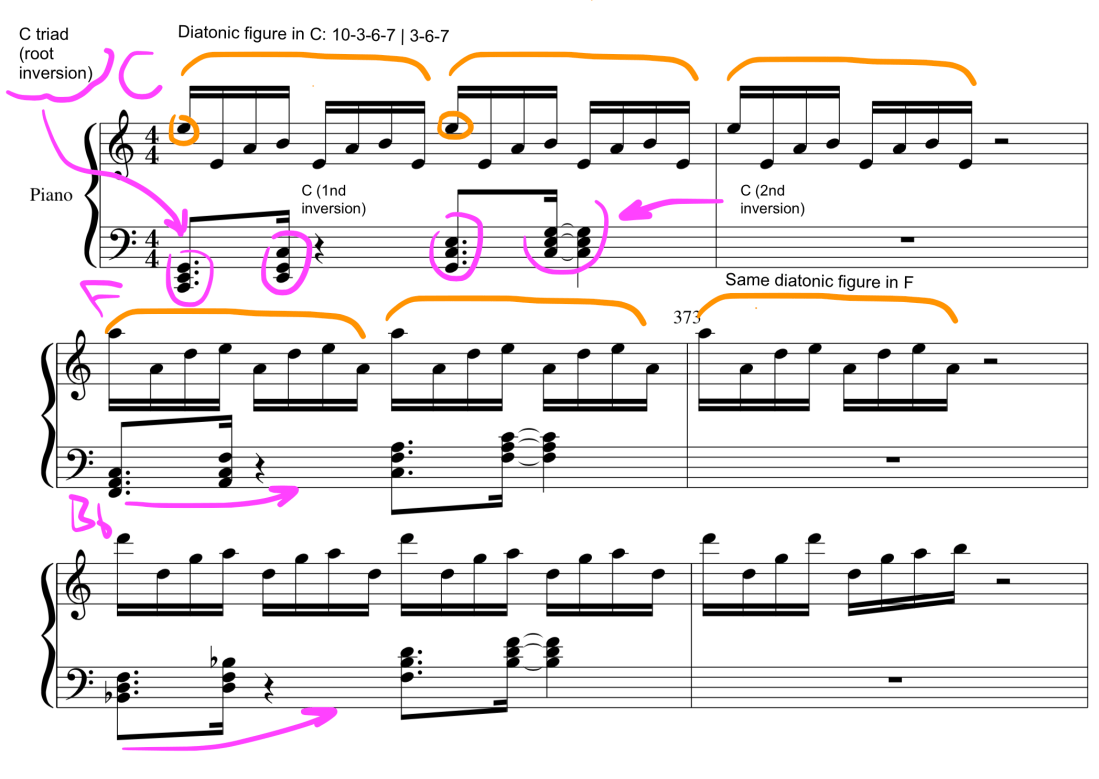

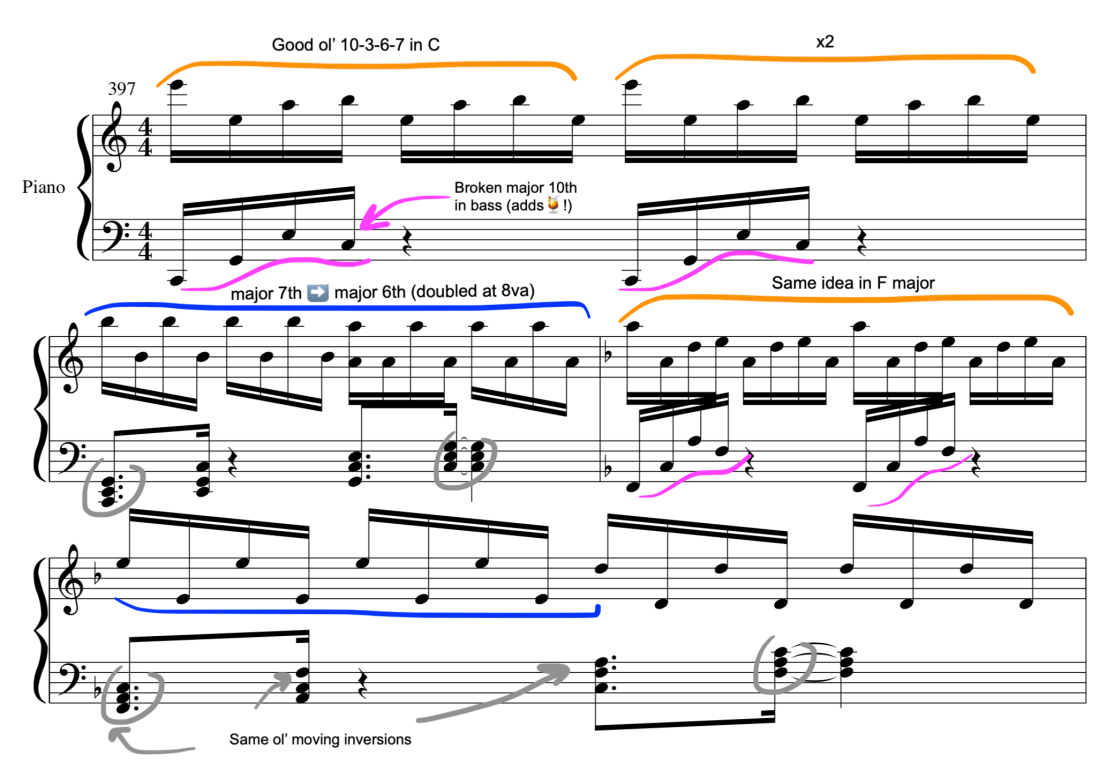

Just doing the same thing, only I added some eighth notes and shells to the left hand pattern. Only using the notes of the corresponding dominant 7th chords (C7 & F7) here. What’s next? Extensions, obviously! How about extending the left-hand pattern one octave lower and adding major 10ths?

I’ve probably said it too much already, but just for the record — broken 10ths in piano is like ollie in skateboarding: once you’ve mastered them, you have access to all the crazy tricks out there. I have all kinds of posts on 10ths here, check them out if you want.

Next stop?

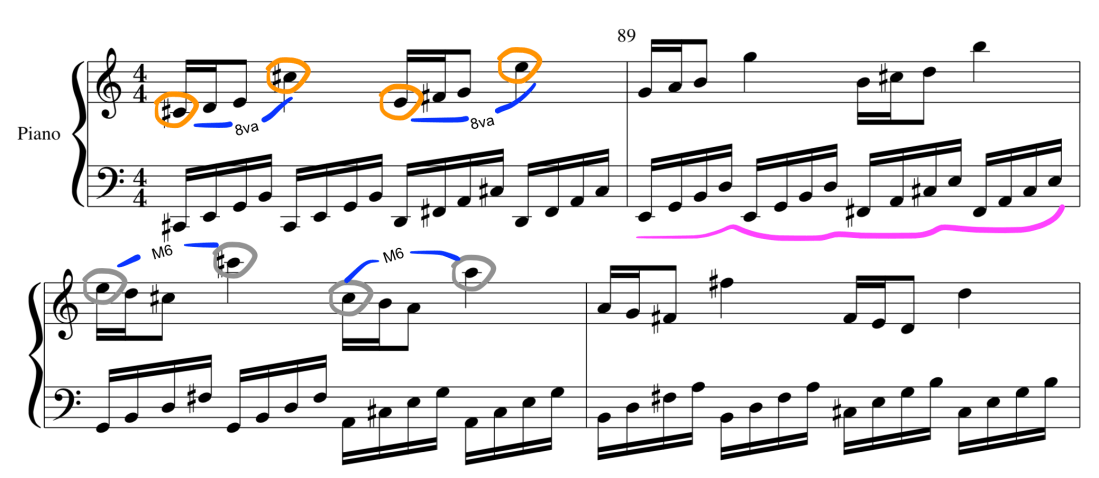

Here, I’ve added one of my new favourite bass patterns that is based on so called “8-to-the-bar bass” that has been used a lot by stride pianists like Willie Smith. I learned it recently from the brilliant book Jazz Piano: The Left Hand by Riccardo Scivales. I’m definitely going to write a separate post to this topic, as it is extremely interesting. But for today, I think that’s it. I love jazz books (although I am not necessarily a jazz pianist), and this the way I incorporate them in my practice routine. Hope you found it helpful too! Thanks for reading and — till later! 🎹